A DRIFT IN THE MERGUI

It’s two in the morning and I can’t sleep. Considering I’ve spent the afternoon in the sunshine, kayaking and drinking a couple of beers with dinner, I ought to be in a deep, satisfied slumber. There certainly aren’t any distractions out here in the middle of the Andaman Sea. A few light beams from the half moon shining out on the water and the occasional creak of the boat as it slowly turns with the evening tide are the only interruptions. Maybe that’s the problem. Out here, in one of the last places in the world to offer a complete digital detox, my urban brain just can’t get accustomed to days without internet, cell phone access, or the lack of any metropolitan stimulation.

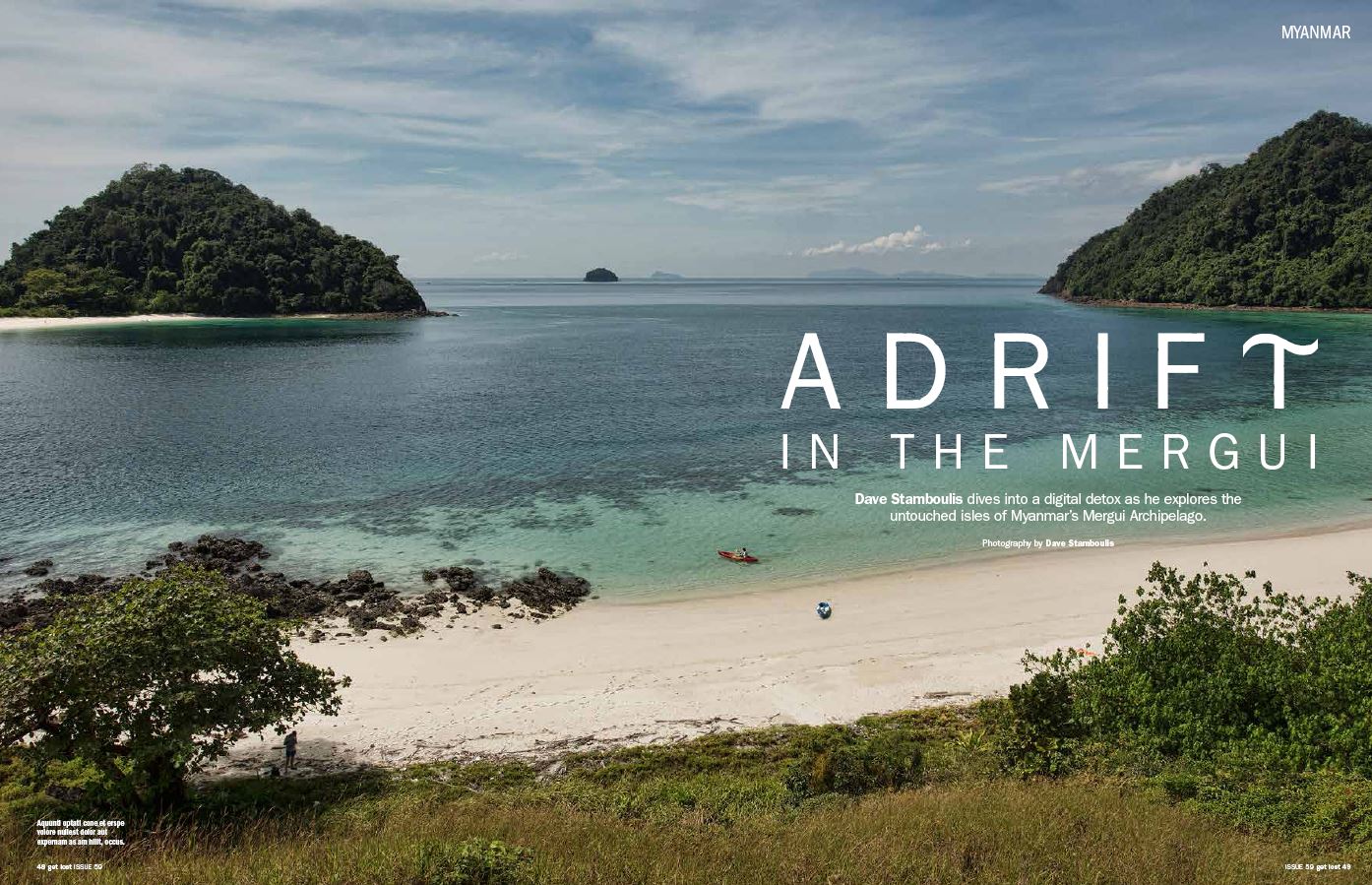

I’m on a liveaboard boat, the MV Sea gypsy, a restored Burmese junk, along with seven other intrepid travellers who are all out to experience the Mergui Archipelago, Asia’s last unspoilt tropical paradise. With over 800 mostly uninhabited islands, the Mergui features a seemingly endless wealth of empty white-sand beaches, turquoise bays, abundant marine life, and plenty of undiscovered dive spots. It’s a winning combination for aquamarine lovers and escapist travellers.

The Mergui was closed after World War ii and didn’t see any outsiders again until Myanmar reopened to tourism in 1996. Still, only a trickle of tourists visit each year. While visas are now easy to obtain, the Myanmar government has kept a tight lid on permits issued for boats and tour operators sailing in the Mergui. Foreign boats have to pay uS$1000 to enter the protected waters, as well as US$ 100 per passenger for a limit of five travel days, meaning that while the resorts of popular Phuket aren’t far away, most of the yachts moored there can’t afford to run charters over for the afternoon.

Bjorn Burchard, who is the face behind our Burmese junk journey, is the owner of island Safari Mergui and Moby Dick tours, one of the few companies in Yangon licensed to run trips out here. He is no stranger to beautiful and remote places. An expat Norwegian, Burchard was the first foreigner to open up a backpacker bungalow on Koh Samui in the 1980s, back when nobody had heard of the island other than a select few nomads who’d gotten wind of an untouched island nirvana in the Gulf of Thailand. Since then, Burchard has seen his fair share of Southeast Asian beaches and isles fall prey to the wrath of the developer’s sword, but he thinks that the Mergui has a chance to get things right, and sees the pristine marine archipelago as one of Asia’s last bastions for sustainable tourism.

“You’ve got some of the best dive spots in the world here, and the recent attention to the environment here by groups like Project Manaia (an ocean awareness project that is operating an advanced sonar system in the Mergui to map and monitor water quality, marine life, and coral regeneration) may get the word out that the Mergui stands for eco-friendly and alternative tourism, offering a pristine travel experience that you can’t get in too many other places,” Burchard says. As dawn breaks, the photographers among us rise silently. With tripods and an array of lenses in hand, we traipse up to the deck to marvel in awe as the sun makes it way to the horizon to create a living artist’s palette of reds, oranges, and every shade in between. Several others make use of the sea kayaks that the MV Sea gypsy tows along, paddling out to embrace the morning light.

As it begins to warm, Jerome, a tall Frenchman who appears to be the reincarnation of one of the aqua-loving Cousteau family, dives from the upper deck into the deep blue, swimming out to island 115, a circular swathe of blinding white sand surrounded by water the colour of emeralds.

On all of the islands that we drop anchor at during the day, from Shark Island (named for its fin-like rock and not circling predators) to massive Swinton Island, full of dense jungle and root-choked mangroves, there is one recurring theme. All of the beaches are empty. Every time our boat stops in the bay and we navigate the tides by dingy, kayak, or swimming, we arrive to feel like an explorer finding land for the first time. Having spent my last decade in Thailand and seeing the changes that have transpired there, I remark to one of my companions that I can’t envision this type of untouched paradise lasting, and as we step onto each new beach I tell him that in ten years we will remember that we sunk our footprints into these powdery sands without another soul around.

Yet the Mergui is not completely devoid of human life. Sailing into a large bay at Jar Lann Island, we are greeted by a fleet of rustic wooden dugout canoes paddling out to meet us, all manned by young Moken girls. The Moken, known as ‘Salone’ in Myanmar, are a group of sea nomads who are famed for their prowess at deep sea free diving without the use of oxygen. Leading a nomadic existence, the Moken have lived for hundreds of years on traditional boats known as kabang, made from large logs and pandanus leaves, and only come ashore during the monsoon.

These days, international borders, the Boxing Day tsunami and politics have forced the Moken to stray from many of their traditional ways. The majority have been settled in government villages in the Surin Islands in Thailand and in a few spots here in the Mergui where they try to keep their connection to the sea by getting jobs on pearl farms or selling seafood to the fish traders from Phuket. It hasn’t been easy – the Mokens are traditionally stateless and nomadic, and feel that if they cannot roam freely, then their culture will disappear. There are few kabang left (national park service rules have stopped the Moken from cutting tree trunks to create them), and ‘integration’ into regular settled society has brought with it ills like drinking, gambling, and theft.

Yet despite the rather ramshackle and impoverished appearance of their village on Jar Lann, the Moken retain their easygoing nature. We’re in awe of the families sitting around laughing, men tending to boats and fishing nets, and women smoking Burmese cheroots while washing clothing. I fall into conversation with a young man named Jao who has worked in Thailand and speaks as much Thai as I do. He tells me these days, village life has improved with several of the locals earning a decent living working on squid boats and selling locally caught fish, but he laments the fact that he has less time to spend with his kids who, he says, can’t dive as well as his generation could and worries about their future.

The Moken villages, as well as attempts to build tourist resorts in the Mergui, are limited by the lack of access to fresh drinking water. This is perhaps the simplest explanation as to why the archipelago hasn’t seen a more rapid tourism development. Only a handful of islands have freshwater streams, and live-aboard charters have to carry large barrels of water to survive one-week outings. Halfway through our sail in the Mergui, we call in at Nga Khin Nyo Gyee, better known as Boulder Island, aptly named for its large photogenic boulders that guard the entrance to one of the Andaman’s nicest bays. Boulder does have a water source, and is home to the rustic Boulder Bay Eco Resort. Here, simple wood and bamboo bungalows aesthetically blend in with the jungle just steps from hiking trails created by the resort, which lead to hidden jungle-overlooks, dazzling serene beaches and azure bays. You won’t find Jacuzzi tubs or spa treatments here, but the communal dining area features fresh barracuda and shrimp barbecues, documentary films about the Moken are shown at night, and there’s even a sporadic internet connection.

The resort is busy supporting a reef restoration project, using old fishing cages to grow new coral. Snorkelling here reveals an incredible array of anemones, blue-lined surgeonfish and striped coral fish, their long dorsal fins wiggling to and fro as they dart through the water. On the trail out to Moken Bay, the island’s most beautiful beach, I spot several Brahminy kites flying overhead, and my solitude is broken only by a group of white-rumped shama, small thrushes with overpoweringly loud and melodious voices, seemingly singing directions to me as I navigate through the forest.

Back aboard the MV Sea gypsy, I marvel at the effects of living without a phone. A week without coverage, living in close proximity to strangers, forces us to reconnect and makes for great friendships. We share candlelit dinners where we bask in long conversations on the open-air deck; we enjoy diving into fictional worlds as we recline in teak chairs to read; and we spend endless time gazing out to sea in what seems to be a forced meditation. Initially, I wondered whether a week trapped in the confines of a small boat would drive a landlubber batty after a few days, but I find the longer I am out here, the more I want to stay.

David Van Driessche, a Belgian photographer based in Bangkok, leads photo tours to the Mergui and is on our trip, scouting out new locations. He’s been out here half a dozen times and says that despite the simple comforts, he never gets bored. “Where else in Asia can you find this many empty islands? Where else can you swim and kayak in the

open sea without fear of longtail or speed boats running you down?” he laughs.

“I probably lose a bit of business due to being out of cell phone range when I come out here, but for the natural wonders and peace of mind, it’s well worth it.”

Before me is an endless horizon, with a storm in the distance on one side, and the red hues of the starting sunset signifying the end of another day. I take one last look at the exquisite blinding white sandbars that make up the nearest islet to our boat, and i couldn’t agree more. It’s more than worth it.

GET THERE

Despite the Mergui being in Myanmar, the easiest and most affordable way to reach the archipelago is via Thailand. Flights to Bangkok with AirAsia start from AU$ 240 one way. From there, for as little as AU$25, Nok Air and AirAsia have several flights per day to Ranong where longtail boats make the 20-minute crossing to Kawthaung in Myanmar. From there, you can board live-aboards and charter boats. You can also fly to Phuket and hire a car or take ta taxi or bus up to Ranong, which takes about four to five hours and costs around AU$11. From Yangon in Myanmar, less frequent flights go directly to Kawthaung. Note that you need a visa in advance to enter Myanmar, which can be obtained online from the government’s e-visa website (evisa.moip.gov.mm)

nokair.com

airasia.com

STAY HERE

On Nga Khin Nyo Gyee Island, Boulder Bay Eco Resort has comfortable bungalows made from renewable materials just steps from the beach and island hiking trails. Rates start from AU$197 per night per person, depending on length of stay and bungalow type, and are inclusive of boat transfers to Boulder Island, meals and use of water equipment.

boulderasia.com

TOUR HERE

Independent travel in the Mergui isn’t possible, unless you’ve got your own boat and are prepared to shell out for the hefty permit fees. The best way to see a significant portion of the island is by sailing on a live-aboard boat. There are also a few islands with resorts that offer transfer services from Kawthaung, although you’ll have to do further touring by boat from the resorts if you want to see more.

Island Safari Mergui offers a variety of Mergui trips, ranging from five-day, four-night island hopping trips on the MV Sea Gypsy for AU$1455 per person to seven-day , six-night trips for AU$2025. Private charters are also available. Packages include lodgings on the boat, meals, guides, kayaks, snorkeling equipment and dinghy transfers to and from the islands.

For photographers looking for off the beaten path photo tours, Dutch photo master David Van Driessche runs trips for all levels of photographers out to the Mergui.

islandsafarimergui.com

davidvandriessche.com